Building a digital archive for the preservation of local memories (with Omeka S), at the intersection of public history and digital history

This post outlines some of the practicalities and the many choices involved in setting up a digital archive for the preservation of the memories and lived experiences of residents of a community in the Alps (Valle dei Laghi, Trentino, Italy). Parts of this post will be particularly relevant to readers interested in the specific platform we are using for our archive (Omeka S), but most of it should be of some interest to anybody considering setting up a digital archive, in particular those doing so outside of established archival institutions.

Some context about the initiative

The Archivio della Memoria is an endevaour characterised by its distinct geographic delimitation as well as by an extensive understanding of what kind of contents should be included in the archive, ranging from old pictures to physical objects, and including recent audio and video materials describing or illustrating local traditions and anecdotes from daily life.

Similarly to what happened to rural and mountain communities across Europe, life in our villages has changed completely for the large majority of residents in the lapse of a few decades. Even if there is a chance that old pictures may be preserved for many years to come in personal collections, with time it would become increasingly impossible to talk to people able to locate them or make sense of what they represent. A significant part of the work at the base of our archive is therefore not only to collect and digitise pictures, documents, or other artifacts, but to give context and detail to these very materials in a way that would otherwise soon become impossible.

In the early stage of the initiative, archivists, historians and others working in museums or adjacent sectors have been consulted, yet no professional historian has been directly involved in producing the actual contents now available online in our archive: https://archiviomemoria.ecomuseovalledeilaghi.it/

Professional historians may smirk at some of the descriptions and the phrasing used, yet they will hopefully recognise this as a source of interesting details and evidence that would otherwise have been irremediably lost.

The Archivio della Memoria is an initiative by the local ecomuseum, the Ecomuseo della Valle dei Laghi, and the outset it received some funding that made it possible to acquire a good scanner, set up the website, and have at least some materials ready to be included in the archive (more details about the donors and timing is available on the archive itself). After that, at its core, it remains largely a volunteer-based initiative.

The working group of contributors has been coordinated by Rosetta Margoni, a retired school-teacher who has long been engaged in public history and has a record of publications on the history of our valley. The website has been originally set up by Roxana Todea. I, a researcher and data analyst with a PhD in Law and Government and no previous experience of public history, have contributed to the conversation on metadata and to the tiny details related to bending to our needs the platform we chose for the archive.

All of us involved in this initiative live in Valle dei Laghi.

Choosing the platform, Omeka S

The reasons for choosing Omeka S over available alternatives are many. They are detailed extensively, in Italian, in this document.

In brief, Omeka S seemed to be the more mature and accessible among open source options for digital archives. We have seen similar initiatives and other digital archives opting for customised versions of established open source solutions (e.g. adapting Drupal to this purpose), but we felt that using a CMS specifically developed for archives would have constantly nudged us towards better archiving practices and facilitated long-term availability of the data at multiple levels. I feel non-open source solutions without a clear path for transfering data to other platforms should not even be considered for digital archiving, which is inherently an effort made with durability in mind.

Omeka has been in existence for more than a decade, and is being developed by (or with the support of) the same organisations that did other excellent pieces of software, including Zotero (a reference manager) and Tropy (a software that facilitates organising pictures and document developed with historians in mind).1

Omeka is being used by a large number of organisations and has a relatively solid user base and core funding. Fundamentally, it encourages using established metadata standards (in particular, Dublin Core), and allows to export data in an easily accessible machine readable format that, should the need arise, facilitates transfers to other platofrms or to other archives.2 I feel this is particularly important for a relatively small initiative such as ours: the ability to transfer systematically the digital archive to a new home may be fundamental to ensure its long-term existence.

Besides, Omeka S is built around the concept of having archive items that can be added to different collections and different digital exhibitions (each with its own website), which seemed particularly well suited to an initiative such as ours including very different types of content.

Metadata for different types of items: different but same

An old picture, a video clip, a bibliographic resource, a physical objects… they all need to be included in the archive consistently, yet there is no one set of metadata that is equally valid for all of them.

The Dublin Core standards are flexible, but in order to ensure consistent data inputs and enable meaningful advanced search options there must be some consistency.

This is enabled in Omeka S by “resource templates”, and we ended up having about 20 of them. You can see how we used resource templates, with the instructions for each use case, in our online instruction manual.

This is one of the aspects that took some work in the early stages, but we are quite happy with the current setup. Archivists have usually a much more defined idea of how an item in their archive looks like, and they often have a pre-defined hierarchy… none of this applied to our case.

Encouraging exploration of the digital archive

Some digital archives tend to resemble search engines: you open the home page and you have little more than a search box. If you are not looking for something specific, but are instead just curious about what kind of materials are available in the archive, this can be frustrating, as random searches may bring only mildly interesting results and mostly do not reveal particularly eye-catching contents.

Beyond standard and advanced search, we propose three different ways to encourage exploration of the archive. All of them are somewhat readily available in Omeka S, but in each of these cases we ended up customising the default Omeka S experience.

Digital exhibitions / mini-sites

Encouraging the creation of multiple sites is a key component feature of Omeka S, and its most distinctive feature from Omeka Classic (a separate verion of Omeka). In brief, you have a shared archive with all contents, and then you can make a selection of these contents separately available to additional sites. Such sites can have a different layout, which is great for digital exhibitions or for showing more nicely a specific type of items.

For example, we created a separate website to present digital versions of local magazines distributed only in our valley. Keeping them separate has two advantages:

- the titles of these magazines often include the name of the village: if someone looks for their own village’s name in the main search box and these were together with other contents, they would likely find a bunch of issues of magazines, rather than the wealth of old pictures that they are probably more interested in.

- Given that these are mostly pdf files, we used a different layout with full-width pdf embeds that would not be as fitting for other contents of the archive.

We currently have nine digital exhibitions, each of them inviting the visitor to explore a separate topic (some of them are still little more than stubs). Creating sites is very easy with Omeka S, but it is currently not as easy to showcase them from a single starting point. To give them more visibility, we used custom html to introduce them in the lower part of the homepage of the main site of our archive, and we kept a slightly smaller reference to them just over the footer in all of the internal pages.

Collections, item sets, hierarchies

Some archives have a distinct tree-like structure, which often reflects the physical location of an item. As ours is a digital-only archive, we have no such inherently consistent structure to give to our collections.

Some digital archives use tags to facilitate finding items that pertain to a specific topic. By default, Omeka S does not have tags, but its concept of “item sets” can be used somewhat similarly. Item sets, however, have no hierarchy, which we felt would have been useful to facilitate the exploration of the close to one hundred categories we identified.

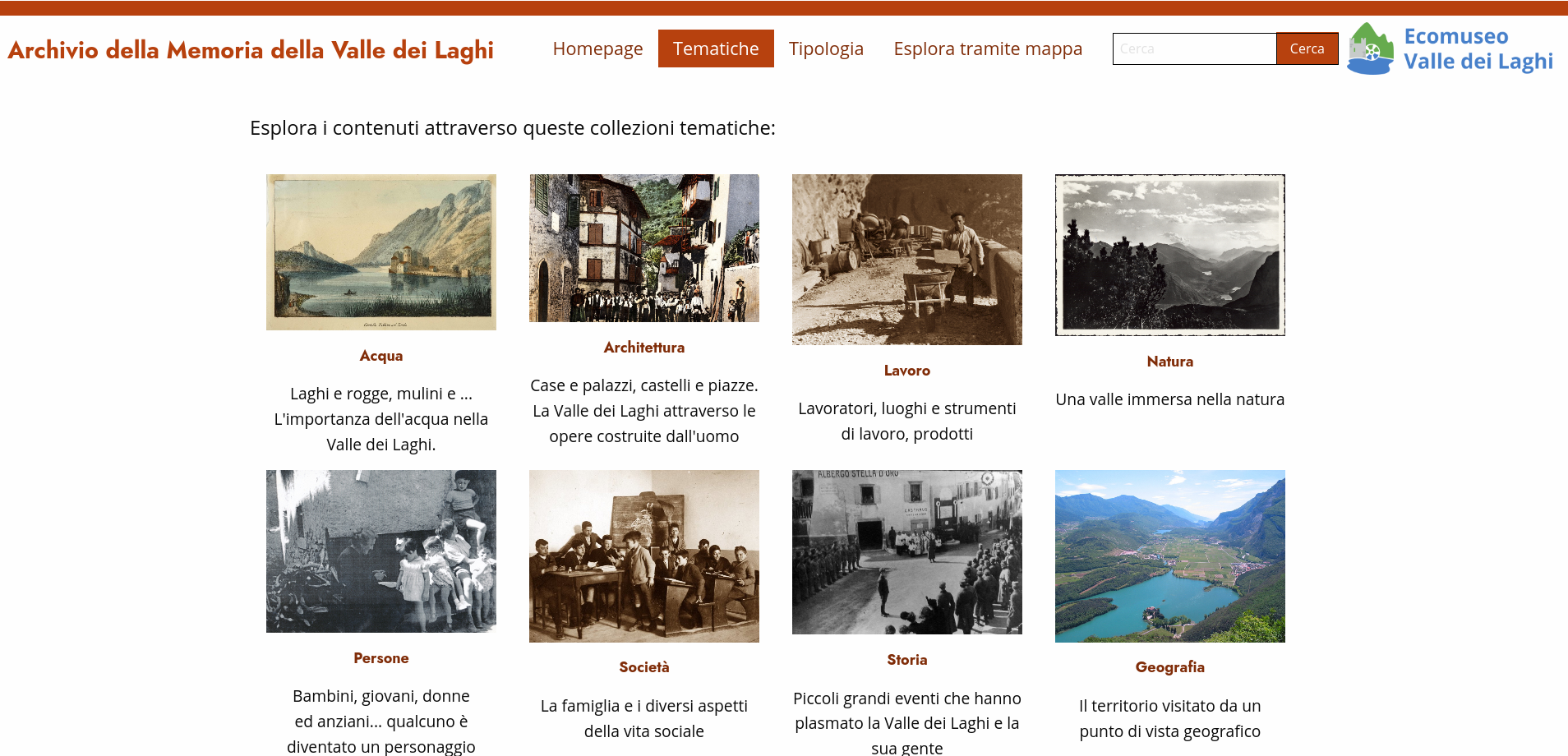

This is the

final solution that we found (people not familiar with Omeka S may want to check out the link, but skip the following few lines). Basically, we set up a “

themes” page on the main archive site, with an “item showcase” widget. Each of the about ten items included there corresponds to a macro-category, e.g. “work”.

The corresponding page, is, technically, a normal Omeka S item page, but that item has included in the field dcterms:hasPart about a dozen item sets. A conditional layout for such pages in the theme showcases these item sets (e.g. agriculture, trade, public works, etc.) nicely, rather than in the classic list format. Single items can thus be put inside more than one “category”, but there is still a hierarchical structure that is reflected in the data themselves and that if necessary can be systematically converted to other solutions. While not explicitly breaking with logic of Omeka S, this pushes a bit what would be the default setup.

We also included a separate page to explore the archive by type of contents, e.g. to see only old pictures or only documents… we accomplished this simply by including links as they would appear from an advanced search.

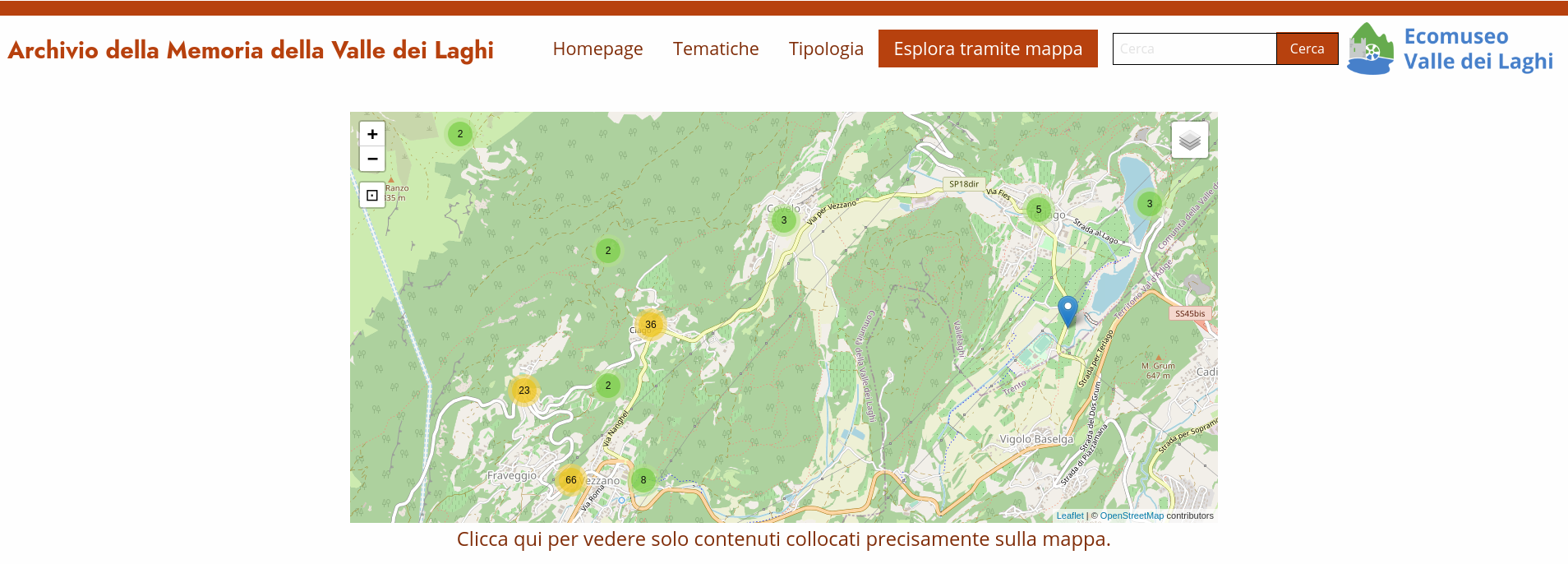

Exploring contents via maps

Omeka S has a mapping module that can easily be added to the default installation. As the vast majority of items in our archive either depict or refer to a specific location, just

browsing around the embedded map is a great way to explore contents. Many will be tempted to just go the map and see if there is some old picture of their street or their own house.

The mapping module is great, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, it expects each item to have an exact location to be pinpointed on a map. In principle, this sounds good, but in pratice, we had to face an immediate problem: what to do with documents or pictures which generically refer to a whole village, rather than an exact location within that village?

I will clarify with an example. Let’s suppose we have a picture of the main square of a village: everything is easy, I can pinpoint that picture to its exact location. But let us suppose that I have a postcard that shows a whole village, or an old document that refers to the water system of a whole village… what do I do? where do I put the pin? Should I put no pin at all, but then the content is invisible to those exploring the archive through the map, or should I put all such pins in the central square of the village (or some other arbitrary location, say, the place where OpenStreetMap sets the village name, or the church)? But if so, I will end up with lots of pins in the central square of the village, and I will not be able any more to find actual pictures of that actual square.

Currently, there does not seem to be a distinct answer to this question in Omeka S, so we ended up with a custom solution: we added a custom metadata field to geolocated items that clarifies if the pinned location is exact or only approximate. In the map browsing page, we added a link just under the map: if clicked, only items whose location is given precisely will be shown.

With this setup, we have the best of both worlds… postcards showing a village can be included in the map, but there is no awkward over-crowding of pins in a specific location if one is interested only in exactly-placed pins.

Cross-referencing items

We suspect that many curious visitors to our archive will reach one way or the other some item that they find interesting. In principle, this could be the end of their journey: they found something interesting, and now they will just hit “back” and search for something else. However, by cross-referencing items, it is possible to turn this into just the beginning of further exploration.

Again, I will clarify this with an example. A village in our valley had a small shop that now does not exist any more. We have the shop itself as an item, with a brief history of the shop and its owners mentioned in the description. A number of physical objects that were sold in the shop are listed in this page as they are recorded as “part of” the shop. A number of pictures in which the shop is visible are listed here as the shop is mentioned as “subject” in the relative page. The shop itself is part of the item set “shops”, and has the name of the village as “location”… and the village itself is an Omeka item… clicking there, will show all items that have that village as location, or clicking on “Shops” would show contents related to all old shops of the valley. All of the above options are clickable and actively encourage further exploration of the archive (do follow the link to see visually how this setup looks).

Other small tweaks to Omeka S

Items and media

Omeka S distinguishes between metadata of an item, and the metadata of a media associated with that item. Puzzling at first, the distinction is important: for example, we may want to keep reference of when a given material was scanned… but the date of the scan is something very different from the date when the original material was created. In other occasions, the media associated with an item simply reflects the item… we felt that in such cases replicating data could be confusing. Eventually, we found a custom solution whereby media metadata are shown if there is more than one media to an item or if a media has more that one metadata field filled.

Besides, by default media have their own separate pages. With our current theme on our main site, media pages should never appear to the user, but with other themes it is easy to end up on a media page, either via the item or because the “browse map” typically includes a link not only to the item page, but also to the media page. Unfortunately, from the media page there is no way to know which item the given item refers to… even more importantly, the media metadata are often very limited and context is missing. To reduce the risk that visitors who end up on a media page such as this one remain stuck without context, we customised the theme in order to always include a link to the original item, and we customised the mapping module in order to leave only link to the item for those who explore the archive via the map. I believe both solutions should be included by default in Omeka S.

Dates and uncertain dates

If you have enabled the NumericDataTypes module, as you should, in order to have dates as actual dates rather than text strings, you may have some issues with the translation of month names if you are running Omeka S with a non-English language. I ended up implementing a

custom solution, but I still feel this could better be handled by the module itself.

More importantly, there is another aspect which is tricky about dates: what to do about uncertain dates. There does not seem to be an agreed standard on how to format these consistently, in particular in a way that still makes the date searchable.

Let’s say, for example, that I have a picture that I cannot date exactly, but, through local knowledge, I can assess that it was taken between 1922 and 1936 (e.g. because of a combination of building and fountain noticeable in the picture that did not exist before or later). How do I write the date in the metadata? Here are the main options:

- nothing: I do not know the exact date, so I do not include it. This would be a pity, because even broad data ranges may be very helpful for others.

- write the date as a text string, e.g. “1922/1936?": this is clear for humans, but is of no use for machines. So if somebody uses the advanced search and wants to find any photo done in a village in the 1920s, this will not appear, because advanced search will just see text there (and text strings cannot be “bigger than” 1920 or “smaller than” 1930).

- just include the information in the description: it’s useful once sometimes finds the item, but it makes it impossible to find it searching by date, same as above

- there are plenty of other solutions we have seen around that can be somewhat machine readable and human readable, e.g. 192x or some variation of it, but none of them looked convincing.

Eventually, we defined as a convention that in each case when we do not know an exact date, we enter twice the date field with the upper and lower boundary, clarifying in the description why this period was chosen if useful. This solution has the great advantage of offering consistent results to researchers using advanced search: if they search for items with date between 1920 and 1930, this hypothetical item would show up, because 1922 is between those two dates. The researcher would then have to judge if it is relevant to them or not, but we think it is correct that it shows up in searches if it may satisfy the criteria.

Finally, if we will end up having to merge our archive with others or if a better standard emerges, this solution makes it relatively easy to convert systematically this format into a string formatted in line with other likely standards.

Website statistics

Omeka S, by itself, has no integrated solution for monitoring traffic of visitors. I have been skeptic about adding something like Google Analytics, because it would have forced us to add one of those odious cookie banners that degrades the user experience and, if done right, is mostly useless.3

Eventually, we decided to go with a self-hosted instance of Plausible, which allows us to collect aggregated data on what are the most visited pages, but does not rely on cookies, never collects private data, and hence does not require any banner. To us, it is still just as useful as Google Analytics or such: it allows to have a broad idea of what people are most interested in, and we have some data on visitors that we can report to perspective donors.

Conclusions

An archive such as ours is a true community, inter-generational effort. It is already involving people from all age cohorts, from school children to the elderly, and gives us all an occasion to talk with each other and find out more about our community, the place where we have grown up or live, and look differently at some of the sights we encounter every day.

After more than a year into this adventure, we are very happy to have started this journey the way we did, and about choosing Omeka S as a base for our digital archive. It did push us towards more consisent use of metadata as we hoped it would, and we now have a rich database with plenty of interrelated contents. The core team of developers and others in the Omeka community have been helpful in providing clarifications or small fixes in the online forum.

With a couple of thousands of items now part of the archive, we feel we are still at the beginning of this long-term endeavour. There may well still be some work to do on the visual aspect of the site, but overall we feel we have a solid foundation and an adequate technical infrastructure that allows for consistent growth as well as for the availability of our archive for the foreseeable future.

-

I am admittedly a big fan of all of these. I have used Zotero for more than a decade, and I have developed a package for the R programming language to interact with Zotero’s APIs. I have contributed the Italian translation of Tropy, and I am responsible for much of the translation of Omeka S done in the last couple of years (but I am not responsible for some less-than-ideal word choices introduced by earlier translators). I have plans to work on a package that would facilitate transferring via API an Omeka S archive to a static website rendered with Hugo, to further ensure the long term and offline availability of Omeka S archives. ↩︎

-

Indeed, data are by default exposed in machine readable format. For example, see this is the machine-readable version of this item page on the website ↩︎

-

Doing it right and legally in line with the GDPR would mean that one would enable Google Analytics only after the user explicitly clicks on a “yes, I want to be tracked” button, with an equally sized “no, I don’t want to be tracked” button next to it; just keeping on browsing the website or closing the banner, as most people do, cannot legally be considered “informed consent”. So if we do this right, our statistics would be almost useless, as few would click on the yes button, and we would still degrade the experience of all users by having an annoying banner. I know many (actually, most) websites are not doing this right, but well… they are wrong. ↩︎