“Abchazja” and other untranslated bits of Wojciech Górecki's Caucasus trilogy

Górecki spent a lavish amount of time in the Caucasus, meeting people across the region and hearing their stories. His Caucasus trilogy makes for excellent reading. Yet, not all of it is accessible to the international readership it deserves

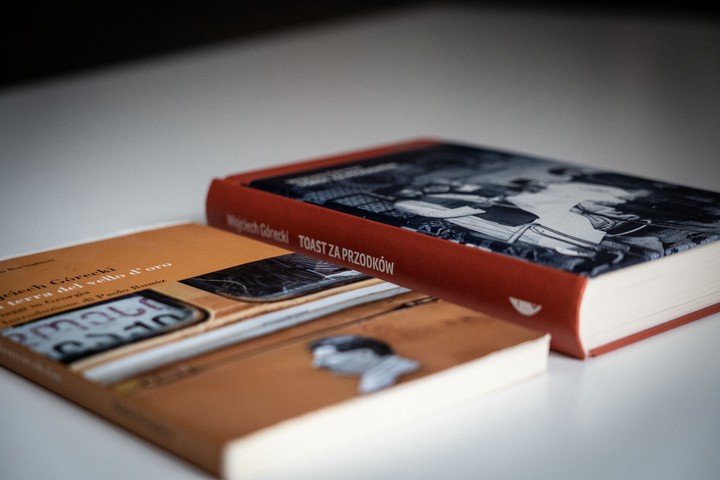

Górecki’s book on the South Caucasus and the Italian translation, including only chapters on Georgia - Picture by Giorgio Comai

Górecki’s book on the South Caucasus and the Italian translation, including only chapters on Georgia - Picture by Giorgio Comai

Originally published on balcanicaucaso.org

Wojciech Górecki’s Planeta Kaukaz on the Northern Caucasus was first published in 2002. It reached Italian readers as “Pianeta Caucaso” (Bruno Mondadori Editore) one year later. His next book, Toast za przodków, published in Poland in 2010, included stories from across the South Caucasus; Italian readers could dive into the chapters on Georgia as early as February 2009, when they were published as La terra del vello d’oro. Viaggio in Georgia (Bollati Boringhieri Editore, translated by Vera Verdiani), but they were never given the chance to read about Górecki’s encounters in Azerbaijan and Armenia. Both of them have sold out, and it seems to be currently impossible to find them in bookshops or buy them from the publisher. His third book on the Caucasus, Abchazja, was published in Warsaw in 2013; it aptly closes the trilogy, even as its starts with the author’s recollection of his first visits to the region in the early 1990s. So far, it has mostly remained unavailable to readers outside of Poland: no English edition has yet come out, nor has it been published in countries such as Italy where previous books have been positively received.

This is unfortunate. Becoming acquainted with the Caucasus and its residents through the encounters of Caucasus connoisseur Wojciech Górecki is a privilege. Enjoying it in full should not be reserved to those who read Polish.

Reading “Abchazja”

Górecki is among the few reporters who visited Abkhazia - formerly an autonomous republic in Soviet Georgia and a favourite seaside tourist destination, now a de facto independent state with limited international recognition - repeatedly and for lengthy periods. His first visit was in 1993, when he was a 23 years old reporter, the war was still raving, and it was yet unclear how things would work out for the residents of the region. In the end, things turned out badly for the Georgians, who were forced to leave their homes. The Abkhaz - before the war, a minority in the region - found themselves in poverty, living in a devastated land, but in a land they felt they could call their own.

Górecki spends time with local residents, and meets many of the public figures that contributed to Abkhazia’s political life in the 1990s. His conversations highlight the hopes and concerns of those who became marginal or central political figures in the early years of Abkhazia’s path to (contested) statehood, as well as the unusual career path of many of them: the fact that Abkhazia’s first president was an historian known for his expertise in Hittitology does not feel particularly unusual in context. The emptiness left by Georgians who were forced to leave emerges from the many references to abandoned houses and cars, and the peculiar approach to ownership that characterised the early post-war years: if an apartment or a car were not being used, it was for someone to make them their own. One of Górecki’s friends from Sukhumi, a Georgian in a mixed marriage who did not take up arms, hoped to return to his apartment on the outskirts of the city from what he thought was a temporary relocation in Southern Russia. He would, however, not be welcomed: somebody else had already taken the apartment. Sukhumi had become a very different city, as well as the main point of reference for ethnic Abkhaz trying to rebuild a new homeland.

The hopes and the disillusion of people who played a role in Abkhazia’s early post-war years, their family histories, the daily life of a member of an urban cultural elite who would keep a degree of mundanity while respecting the practices of Abkhazia’s social norms as well as taking up military committments… these are the kind of stories that fill Abchazja‘s pages. Ultimately, it is the direct recollection of the individual and collective experiences during these troubled times, in some instances following-up with the same interlocutor year after year, that most characterises the book.

Taking the time to walk, to travel by train or by car, to meet people, to spend time with them, and create the circumstances for these meetings to open the way to relationships of trust and friendship is what makes Górecki’s writing unique.

A frequent feature of book-length reporting is that of resembling a journey: the author visits a place, meets someone interesting, tells a fascinating story, and moves on. But here’s the catch: they rarely get back. Not Górecki: he spends lavish amounts of time in the region, and enjoys returning to the same places and meeting some of the same people, without feeling the need to rush towards some new adventure.

This diachronic dimension appears most evidently in his Abchazja, but the fact that the author was in no rush is a common feature of the whole Caucasus trilogy. I particularly enjoyed some of the (untranslated) chapters on Azerbaijan in his volume on the Southern Caucasus, Toast za przodków , because they present broader societal trends through the recollection of rather mundane moments such as looking for an apartment to rent. They are an antidote to a disappointing, yet common feature of contemporary reporting, based on correspondents rushing in and out of conflict zones. Górecki lived in Azerbaijan for five years, and he does not need disruptive events to tell a good story. Indeed, his Caucasus trilogy serves as a good reminder that good reporting does not need to feel like an action movie or a quest.

To be fair, Abchazja does have some action, perhaps inevitably so, as the first chapters are based on reporting conducted when the author was in his early twenties, bursting with curiosity and short of money, at a time when war dynamics in the context of the collapse of the Soviet Union introduced a considerable amount of uncertainty in any outing, not to mention the inevitable border crossings.

Different readers will find different things in this book. There is definitely something for the (presumably small) international audience with substantive interest in Abkhazia, and enough knowledge about the place to recognise the names of Górecki’s interlocutors and appreciate their role in public debates about Abkhazia’s future perspectives, the intra-elite disagreements and reciprocal accusation as well as the endless debates about Russia’s presence and influence in the region.

The book is however written with a broad audience in mind, and adequate context is given to make the book accessible and enjoyable to readers that have no familiarity with the region. Those who know little about Abkhazia will be given the chance to hear about the stories that a small Caucasus people such as the Abkhaz tell about themselves, their historical and contemporary myth-making, their attachment to Abkhaz “traditional religion” (a rather widespread local form of paganism) as well as their fundamental preoccupation with the long-term survival of the Abkhaz language, culture, and people.

Similarly to what he does in the other parts of the Caucasus trilogy, Górecki does not feel compelled to express sympathy or criticism to a specific narrative. The reader is not left without some reference to make their own judgement, but each of the persons met by Górecki has their fair chance to tell their story and their own understanding of events present and past directly to Górecki’s readers. Again, this is a pleasant escape from some international reporting in which voices of interviewees seem to be stylistic props in a narrative distinctly set by the author rather than protagonists given the opportunity to actually tell their story on their own terms. Some of the stereotypes and myths that Caucasus residents like to tell about themselves are reported and sometimes not explicitly contested by the author, if not humorously, but this seems to be part of what makes these books honest not only towards the reader, but also towards the author’s many interlocutors, companions, and friends in the region.

In the very last brief chapter of Abchazja, Górecki finally leaves some room for self-reflection. As an established Caucasus expert, having worked for years with Poland’s diplomatic service and then with a government-funded think tank, he is now invited to high-level conferences in fancy hotels in the region. He distinctly feels that he cannot do his work as a reporter sharing the life of his interlocutors while spending his nights at the Marriot’s. Perhaps, he also needed a break from the region… after two decades focused on the Caucasus, Górecki decided to explore the lands on the other side of the Caspian Sea, and in 2018 he published a book on post-Soviet central-Asia ( Buran, again, untranslated in Italy).

Translated and untranslated Caucasus bits

All things considered, Górecki’s trilogy is possibly the best way for the uninitiated to meet the Caucasus from afar through a mix of reporting, encounters with its residents, and gentle historical digressions.

As of 2020, there is a substantial and accessible bibliography that scholars and students with an explicit interest in the region can refer to if they wish to learn about history and contemporary politics in the Caucasus, but actually very little I would be able to recommend to an acquaintance who asks why I find the region so fascinating. Górecki’s writing does not unduly focus on current events, and ages well: the external appearance of the big cities of the region may be changing fast, but the life stories spanning generations of their residents do not. Besides, Górecki is obviously interested in the more distant past and seems to have a penchant for small communities with an unusual history, such as the Nekrasov Cossacks (old believers who fled to the Ottoman Empire in the 18th century whose progeny “returned” to the land of their ancestors in the Soviet Union in 1962) or the Udi people, a small community of mostly Christians many of which now live in an Azeri village, whose contemporary condition is an invitation to explore the complex history of the region.

Among the reasons for the enduring relevance of Górecki’s Caucasus trilogy is the fact that, as it turns out, writing about the Caucasus does not necessarily mean writing about conflict in the Caucasus. While inevitably present, conflict and warfare are not the central component of Górecki’s depiction of the region, nor are they a constant point of reference.

By telling the stories and experiences of contemporary residents of the Caucasus as well of their ancestors, Górecki’s books serve as an excellent reminder of how fascinating this region is, because of the incredible density of languages and traditions as well as the great diversity in lived experiences and family histories that can be heard to this day travelling between the Black Sea and the Caspian. A troubled past and painful historical circumstances may be part of what makes some of these stories so extraordinary, but recent conflicts need not be the lens through which a reader meets the Caucasus.

Solid reporting, excellent writing, new revised editions in Poland, sold-out translations in Italy, and parts of his work translated in other countries… more international publishers may well take their chance to make Górecki’s Caucasus trilogy available to readers outside of Poland.