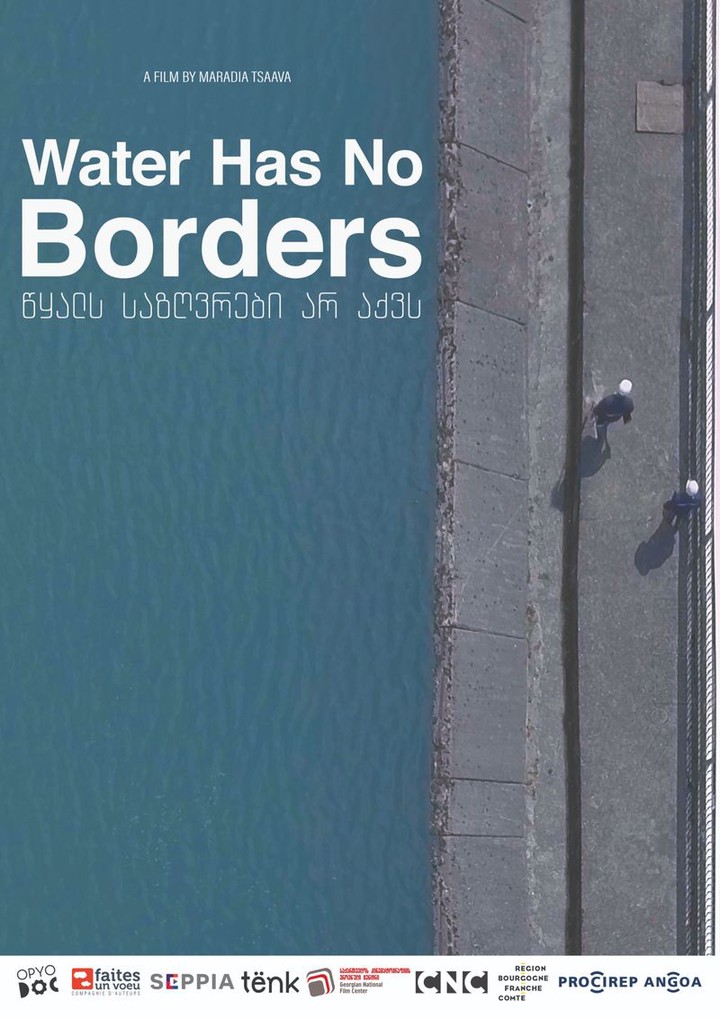

"Water has no border", even along the Inguri - A documentary (brief review)

“Water has no border” - a 2021 documentary by Maradia Tsaava. See trailer and synopsis.

Seen at the Trento Film Festival in May 2022.

Crossing the de facto border (also known as administrative boundary line) between Abkhazia and Samegrelo is not so easy - unless you are water, or you work with water: employees working on the hydroelectric powerplant cross the border routinely.

“The other side” is just a few hundreds meters away at most throughout the film, and yet, seemingly unreachable for the film’s protagonist (Maradia) and her crew. A bureaucracy with no transparent rules for entry is the most direct obstacle to a daily excursion to the powerplant located in Abkhazia. And yet, Maradia’s inability to cross the border, day after day, still feels like a minor nuisance in comparison to the painful experiences and memories of the people whose life has been broken by the border and the events that led to its creation.

How difficult is it really to cross the border? Even for local residents who do cross it somewhat regularly, the answer to this question has changed considerably in recent years. Even before the extended closures supposedly related to Covid-19, crossing of the border could be closed, or access limited, for a number of reasons. Unpredictability and a degree of arbitrariness are, implicitly, a key component part of the border policy imposed by authorities in Sukhumi. A tightly regulated border with few “official” crossing points is also consequence to Russia’s policing of the border and Russia’s own preferences in this regard.

Throughout the documentary, such considerations remain, however, in the background. Politics and policies are not discussed explicitly: the apparent focus remains on an administrative decision to allow or not allow the border crossing, which could seemingly go either way. And even this key aspect slowly drifts into the background as personal stories and painful recollections take centre stage.

We are then left with the majesty of the dam and the machinery that controls it, and water, with its brutal and natural force.

Recommended to…

For people who are very familiar with the context, this documentary is unlikely to offer new insights. Some of the protagonist’s experiences will also feel very familiar to those who travelled to the region. The documentary focuses on the life of local Georgians, and the dialogues are almost completely in Georgian (even if a characteristic switch to Russian expressions appears repeatedly in dialogues involving elderly women working at the dam). Experiences from other communities living on “the other side” of the border remain - understandably, given the focus of the documentary on the area around the Inguri e and the broader circumstances - out of reach.

For viewers who are less familiar with the context, the personal experiences that form the core of the film will open new questions about local dynamics; certainly, they won’t offer explanations about the situation. The underlying feeling of suffering caused by the war, and specifically by the border, is certainly a big and important part of the story.

Both kinds of viewers will appreciate the beautiful and powerful images of the dam, and the personal touch stemming from the interaction with people working there. Minute after minute, what might have started as as a journalistic feature about the dam, turns into more intimate dialogues and recollection of stories of the people who live across the border. The dam, its impressive size, and the power of water, are a constant presence.

The film is nicely shot, with quality images, colour, and audio recordings.